Answer to Map #73

Click here for a full-size version of this week’s map.

Back to this week’s maps and hints.

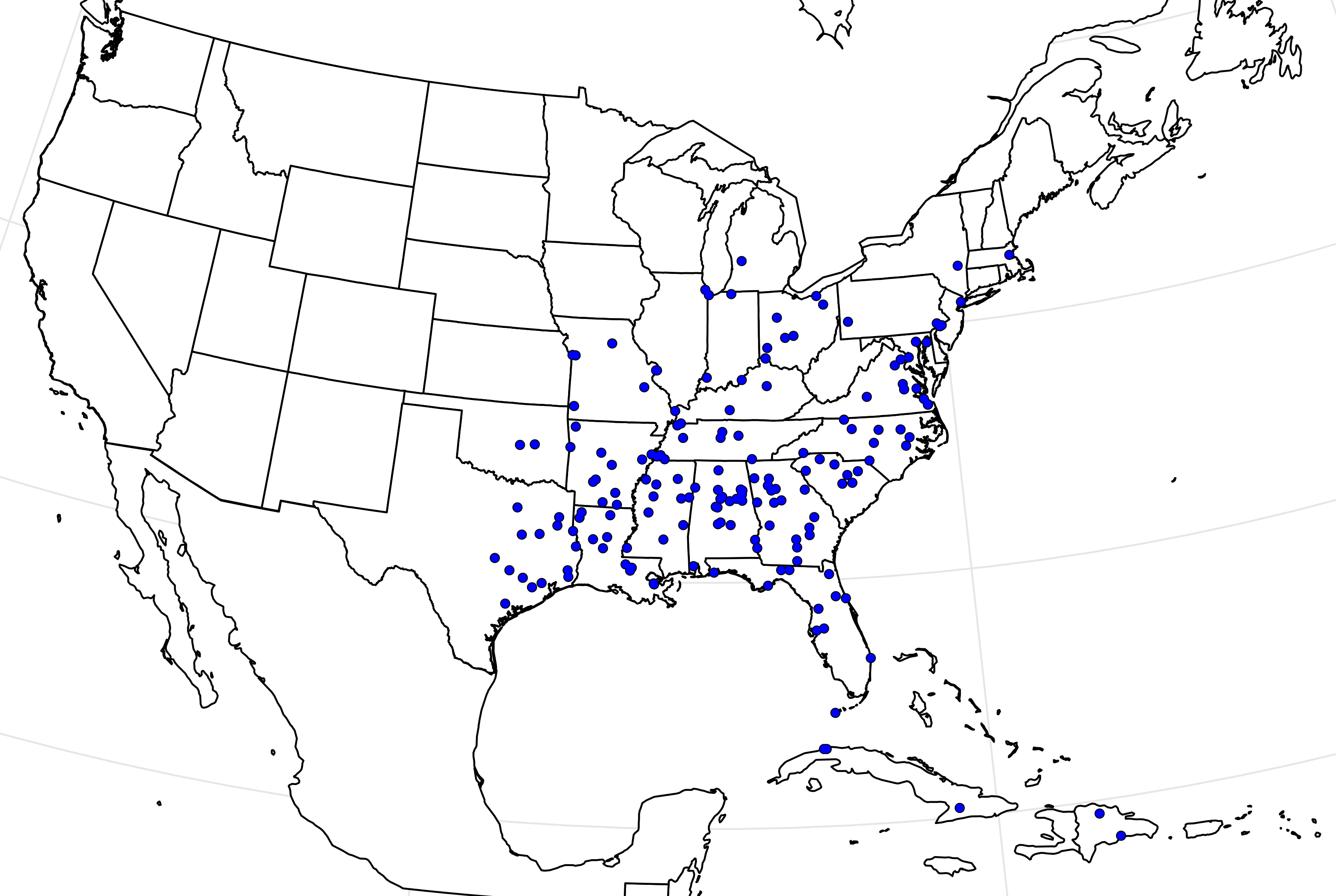

Answer: This week’s map was a dot map depicting the birthplaces of all baseball players in the Negro Leagues in the year 1942.

Until Jackie Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947, a “gentleman’s agreement” among the owners of the various teams ensured that African American players were not welcome in Major League Baseball. Consequently, many African Americans who wished to play baseball formed their own professional teams, which banded together to compete in segregated leagues. There were several such leagues that came and went, but our focus is on the highest level of African American competition in 1942.

Why 1942? It’s an arbitrary year, but we chose it because that was the year that the Negro World Series was revived after a long hiatus. That year, the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro American League swept the Homestead Grays of the Negro National League in a four-game series. Some of the most talented players in the history of baseball took part in that series. The Monarchs’ best pitcher was Satchel Paige, who eventually got his chance to play in Major League Baseball at the age of 42; he retired from the majors at 47 but continued to play baseball professionally until he was 59. In the 1942 Negro World Series, Paige had to pitch against catcher Josh Gibson and first baseman Buck Leonard. Gibson is notable for the fact that he probably hit more home runs as a professional than any other baseball player in American history—around 800 in the various leagues in which he played. He never got the chance to play Major League Baseball.

It is difficult to find reliable statistics about the Negro Leagues because the game results were not always widely reported. The best database where you can find information is Seamheads, a site that has a wealth of articles and historical photographs as well as statistics. To make this map, we simply wrote down all the known birthplaces of players who were active in 1942, then plotted them on a map by latitude and longitude.

Perhaps the most obvious feature of the resulting dot map was that most of the dots were clustered in the South. Their patterns reflects the distribution of the African American population of the U.S. in the early twentieth century, before widespread migration to work in northern cities. You also may have noticed that there are no dots at all in the western U.S. That’s mainly because there weren’t that many African Americans in the West at that time (also, the population of the West as a whole was much, much smaller).

There are a few dots on this map in Cuba and the Dominican Republic. These dots hint at several different interesting stories. First, you may remember from Map 48, a map of the birthplaces of current Major League Baseball players, that baseball is very popular in the Spanish-speaking Caribbean. Although professional baseball in the U.S. has become more internationalized in the past few decades, the interest of people in those countries in the sport is not new.

Second, it’s important to realize that a lot of African American players also participated in leagues in the Caribbean, especially in the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico. Players didn’t receive as much money for playing on Negro League teams, so they often had to supplement their incomes by playing in several leagues in a year. The Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico hosted winter leagues that attracted some of the world’s top talent.

Third, there are many people in the Caribbean of African origin who have black skin. A lot of great baseball players have been Afro-Latinos (that is, Latinos of African heritage) from the Caribbean—including Hall of Famers Roberto Clemente, Orlando Cepeda, and Juan Marichal. These players sometimes had uncomfortable adjustments to Major League Baseball. Cepeda once told an interviewer, “We had two strikes against us: one for being black, and another for being Latino.” Another Afro-Latino player, Minne Miñoso, recalled in one autobiography that he got in an argument with one African American teammate who insisted that Miñoso was not really black.

All this brings us to the story of the Cuban Giants. In 1885, a group of African American baseball players in New York formed a team. None of them was from Cuba. There are lots of stories about the origin of their name, which was given to them by a promoter to make them sound exotic. When they went off on road trips, they discovered that they were perceived as “foreign” because of their name. In some cases, they spoke gibberish to each other on the field and pretended it was Spanish. As a result of being considered “Cuban” instead of African American, they were sometimes treated differently. The team also traveled to Cuba in the winters to play against teams there. Eventually, a team descended from the Cuban Giants, now called the New York Cubans, became a member of the Negro Leagues. And, owing to the bizarre connection to Cuba that the team of non-Cubans had built up by calling themselves Cuban, some Cuban and Dominican players flocked to join their team. Only one of the dots in the Caribbean on this week’s map indicates the birthplace of a player who played for a different team rather than for the New York Cubans.

Next map: Click here to try out our newest map question.